Breakable: Wrestling With One’s Own Mortality

7 min read

For a good deal of one’s early life it’s easy to consider that you might just live forever. This is especially true if you’ve not been touched by death very often. But, inevitably, one grows older and starts to notice that, physically speaking, some things just can’t be accomplished as easily as they once could. Your own parents, who you assumed would always be a part of your life, don’t look quite as sturdy as they once did, and you begin to understand a universal truth… people don’t live forever.

For a good deal of one’s early life it’s easy to consider that you might just live forever. This is especially true if you’ve not been touched by death very often. But, inevitably, one grows older and starts to notice that, physically speaking, some things just can’t be accomplished as easily as they once could. Your own parents, who you assumed would always be a part of your life, don’t look quite as sturdy as they once did, and you begin to understand a universal truth… people don’t live forever.

This understanding became abundantly clear to me one day in December of last year.

“You’re going to need surgery.”

The pulmonologist’s words filled me with instant dread. I hadn’t exactly been given a death sentence. I didn’t have cancer or anything like that. But it was my first time in the hospital, and I was as worried for my life as I’d ever been before.

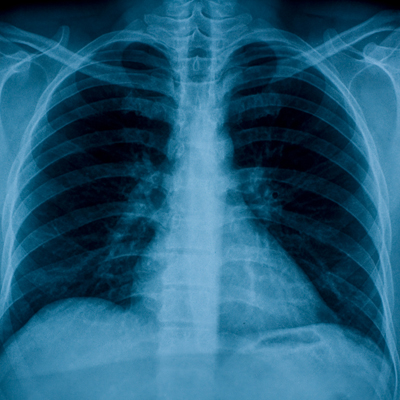

For two weeks prior to being admitted to the hospital, I’d been having some pains in my side. The pain was more acute when I would take a deep breath. It didn’t seem serious at first, and I assured myself that it was some kind of muscle strain. After about a week of this I went to the doctor. They did some basic tests and couldn’t find anything seriously wrong with me. It didn’t appear to be my heart, and I hadn’t been having any symptoms other than pain. They offered to give me a chest X-ray, but I declined thinking it was nothing serious. I went home and started taking over-the-counter pain pills to handle the discomfort.

Over the next week I started having a low-grade fever, but I still didn’t think there was anything seriously wrong. The ibuprofen had been helping with the pain somewhat. Then, early one morning, the pain in my side increased ten-fold. I knew then that something was wrong, and I went to the emergency room. After several hours, a doctor informed me that I had about a liter of fluid in between the lining surrounding my lung and the lung itself. I was told that this was most likely a complication caused by pneumonia, a pneumonia to which I’d been completely oblvious. This build up of fluid was causing my lower right lung to collapse.

I was admitted to the hospital, and, though I was worried, I was hopeful that I would only be there for a day, two at most. After a few days of lying around, hooked up to impossibly inconvenient tubes feeding me antibiotics and fluids, my hope began to deteriorate. It was decided that they would try to extract the fluid by inserting a needle through my back, aided by an ultrasound machine. This procedure ultimately failed as the majority of the fluid had congealed. It was not long after that that I was being told I would need to go under the knife.

Almost a week after I’d been admitted to the hospital I had my operation. Three incisions were made in my side. With the help of a camera, tubes were inserted into the affected area and the fluid was extracted. My lower right lung was reinflated using suction.

The surgery had been on a Thursday. Friday was lost to me forever to a drug-induced haze. I remember being awake at times, feeling the chest tube down my throat. I was aware of not much else, and, during those times, I just concentrated on breathing, in and out. It was a horrifying, trapped feeling. Fortunately I spent very little time in a state of moderate awareness. At some point they removed the chest tube, and I slowly started to regain consciousness. I wasn’t in much pain, but that was only because of the massive amounts of drugs I’d been given.

I was told that the surgery went well, though a tube was left in my side to drain off any excess fluid that was lingering. I only spent one more day in the Intensive Care Unit, but it would be another week before I would be allowed to leave the hospital.

This story might not seem like much, and it’s definitely not nearly as bad as some people’s experiences. But the biggest struggle for me during this trial was not the actual physical problem itself or the surgery and the subsequent recovery (though those things certainly factored in to everything). My biggest struggle was the dark cloud that assaulted my mind, the near-paralyzing fear that threatened to rip apart my psyche and the ultimate realization that my own end would come and maybe sooner than I would like it to.

A hospital is a lonely place. After a while the walls seem to close in on you, and, when the visitors have gone home and you are no longer able to distract yourself with television, you are left alone with your thoughts which can go to very dark places. At times it seemed as if I would never recover. I couldn’t remember what it felt like to be whole, and I genuinely feared that I would never leave the hospital.

I became acutely aware that I was breakable, and even if I survived this experience, my life could be easily extinguished in any number of ways. It’s not that I minded the thought of dying so much, but I certainly didn’t want to shuffle off this mortal coil having achieved so little, having left no discernible mark on the world. Despair swallowed me whole. It was irrational, but I was helpless to stop it.

I honestly believe that if I had not had my family with me, I might have perished there in that prison they call a hospital. My parents flew across the country to be with me, and I couldn’t have been more appreciative of that. And when I felt I was at my darkest, it was my mother who reminded me of this Psalm:

Bless the Lord, O my soul,

And all that is within me, bless His holy name.

Bless the Lord, O my soul,

And forget none of His benefits;

Who pardons all your iniquities,

Who heals all your diseases;

Who redeems your life from the pit,

Who crowns you with lovingkindness and compassion;

Who satisfies your years with good things,

So that your youth is renewed like the eagle.

These words became a mantra, and I reminded myself of them every day. My body had failed me, and my mind had become weak with fear. All I could do was hope that God would restore me. It was all I had.

Eventually I was able to walk around the hospital some and was encouraged to do so to strengthen my lungs. It was during these walks that I realized I had obtained a newfound empathy for people who had to endure suffering. One night I passed by another hospital room, and I could hear its occupant sobbing uncontrollably. In that wailing I heard all the fear and loneliness that I myself had felt, and I wished there was something I could do. I knew that I would never look at people’s suffering the same way.

When I was finally released from the hospital I discovered a new fear, the fear that I would never recover fully or that the problem that had put me in the hospital would reoccur. A type of post traumatic stress that is experienced by many who go through extended hospital stays, this new fear would keep me up at night. There were times when I would be afraid to go to sleep because I believed I might not wake up.

Eventually, as I got better, little by little, this fear subsided… but not completely. Encouraging follow-up appointments with my thoracic surgeon began to convince me that I was going to be okay. But it’s been more than two months since my release from the hospital, and I still don’t feel “normal”. I still have fairly consistent aches and pains. When I breathe deeply, my right lung feels tight and uncomfortable. And there are days when that fear creeps back into my mind and tells me that I’m moments away from a relapse or something worse.

All I can do at those times is put my life in the hands of something bigger than myself and try to put fear out of my mind. It has always been fear that has paralyzed me and kept me from living life the way it was meant to be lived. And if this experience has taught me anything it is that I don’t want to be enslaved to that fear any longer. And who knows? Maybe I can help someone else overcome those same fears as I continue to overcome them. At least then I can say that I’ve for once done something good in the world. And if my flame is extinguished too early, at least there will be that.

So true, the reality of imortality. So glad you made it through so well.